I like my own freedom to do what I want without anyone telling me what to do. I feel we all want our space. My work has that feeling of really wanting its own space. My paintings are about freedom. *

Freedom and Democracy

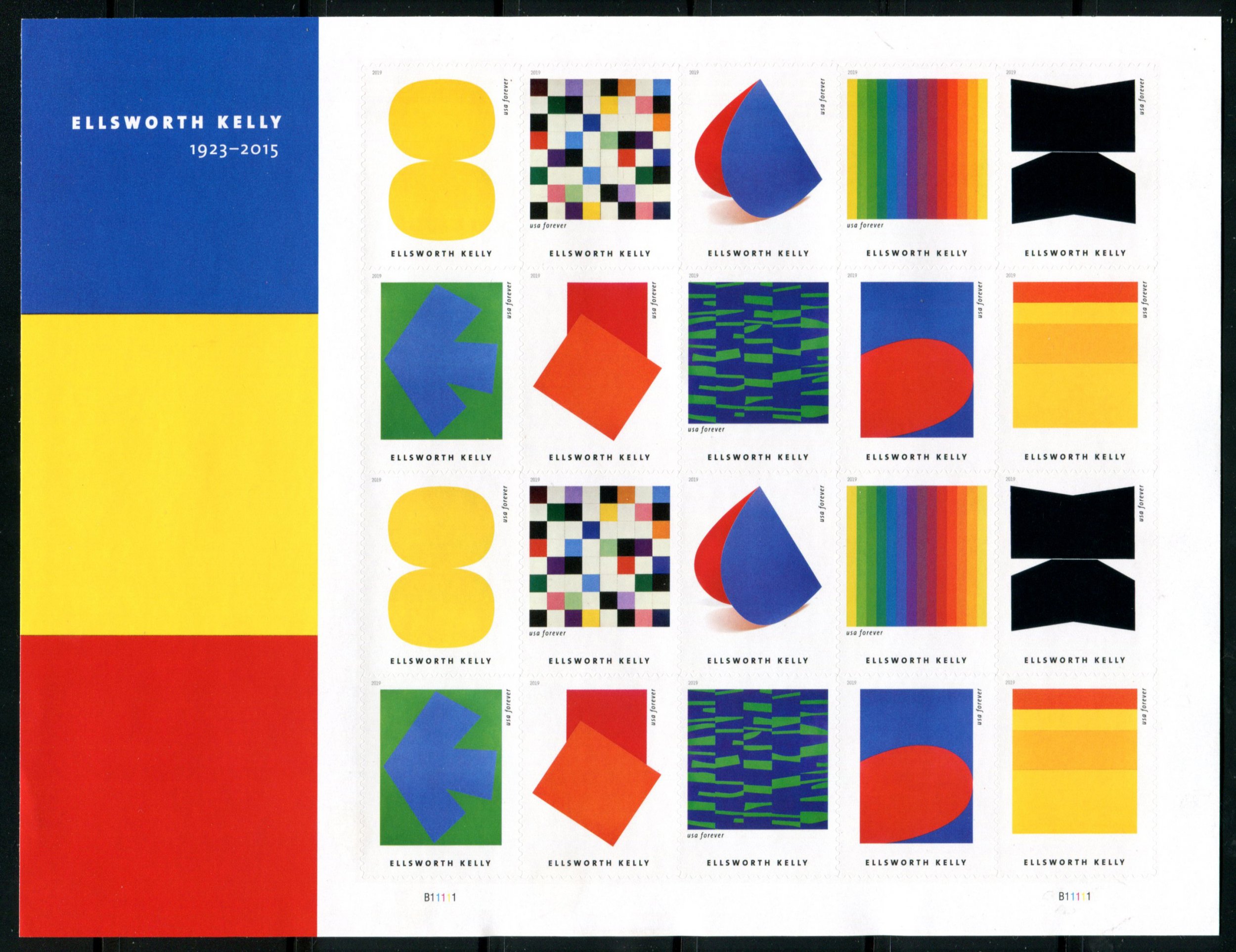

Ellsworth Kelly (1923- 2015) always did art his own way—a consistent study of human visual perception: the interaction of color and form in our eyes and brain. Luminance is very important in his art—which often gives the sense of movement in the corner of our eyes. This is also what the Impressionists did. In today’s neurobiological research, scientists are starting to analyze Monet’s art:

Some of the color combinations the Impressionists used have so little luminance contrast that they create the illusion of motion […] Artists must learn to see luminance gradation and to evaluate luminance independent of color. Even then, they often find it impossible to duplicate those luminance ranges with pigment. — Margaret Livingstone, Harvard Medical School (2003)

Vision gives us freedom—we can choose to close our eyes, or walk away from a painting. We can even look without seeing. It is not as easy with music. Sound and speech are also linear: we need to stay around to get the message. This is not true with art, image, or our surrounding: we are free to see—more, or less, or not at all.

Art, and our vision thus offer us ultimate democracy. We can also choose to make our own art.

Kelly’s Words (His Last Interview, 2015): .

My paintings have never gone sky high [in price], and perhaps that’s a good thing. My dealer feels the people I sell to are interested in the work, rather than in the investment.

I felt very much that painting [in the 50s] was too personal. I wanted to do anonymous work, like the old masters. [He said he was not particularly fond of Jackson Pollock’s art]. **

[On his return to New York from Paris in 1954] The abstract expressionists didn’t use colour so much, and I wanted to bring it back in some sense. What I also always say about them is that they found their picture as they made it – the process led to its shape – whereas I had to have the shape first.” In his first year, he was able to pay his rent only thanks to a loan from his friend, the sculptor Alexander Calder.

[On old age] His appetite for work, though, remains keen. I give what I’ve got. It’s harder. I can’t work on really big pictures any more, so the ideas are blocked a bit. But then, the visions were always too much. He waves a hand. I feel like the world is over there, and it keeps coming at me, and I want to do it, respond to it.

[Interviewer’s note] He has questions, too—and this is what I will remember later: his abiding interest in other people, other things. Curiosity often abandons the old (or they abandon it), but he still looks outwards, brightly.

On Kelly (From my Blog):

Yes, art is democracy at its deepest level… That freedom includes art for everyone—in the truest sense of the word—the sharing of our common visual perceptual processes, the eyes and the brain. — Do Scientists See Art (2010)

And the late Ellsworth Kelly’s colorful, simple geometric forms continued Monet’s examination of our visual perception: color, form and how they affect each other in our eyes and brain. — Harvard’s New Admissions Policy (2016)

Back to Paris, and Monet, in Musée de l’Orangerie. The old orangery was converted in 1922 to house Monet’s definitive waterlilies, which he gave to the French nation. To many visitors’ surprise, for the first time in almost a century, the immersive gigantic waterlily paintings are introduced in the small entrance rotunda by an early Ellsworth Kelly (USA, 1923 – 2015), Tableau Vert (1949, Art Institute of Chicago). Kelly had made the piece after visiting Monet’s Giverny and seeing the elder artist’s late works, piled in an abandoned green house. Kelly probably considered his own mostly monochrome and clear-edged works landscape and acknowledged Monet’s influence in his own oeuvre. — On the Wall and More (2018)

In this sense, Kelly could be called the true heir to Monet’s impressionist art, particularly the late ones that Monet (1840-1926) himself did not like. Monet probably arrived at his abstraction by accident of his cataracts and general age-related decline of eyesight, as evidenced by his own rejection of his late works, many of which had been saved by family members from his own destruction. — Monet and Kelly (2015)

Ellsworth Kelly, whose art is basically a consistent visual study of this abstraction possibility says: If you look with your mind turned off, everything becomes abstract. — My Father is the Late Monet (2012)

Yes, that freedom is also the American ideal: the same freedom for us—and for others.

And if we see well, we’ll also be less quick to judge others.

* Stamps don’t tell all: one needs to experience his art in a gallery or museum, to feel that sense of movement when one is immersed in it.

** Kelly mentioned how, as a student in France, he was very impressed with Byzantine mosaics: the flatness and the anonymity of the artists.