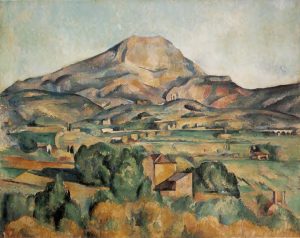

Mont Sainte-Victoire (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1885/1895) Paul Cézanne (French 1839–1906)

Keep your eyes at one of the dark spots in the painting—you can feel the whole landscape swell up around you, as if you’d just entered the picture. That’s Cézanne’s discovery—his petite sensation which he described as pater omnipotens aeterna deus [omnipotent, eternal father God]. And neurobiology has only just now caught up with him.

Cézanne had entered the unconscious—the viewing of a scene through one of the visual pathways which originate in our primary visual cortex in the back of the head. It is the pathway that is largely color-blind and does not name objects; only concerned with their location and form which are defined by tones (luminance values)—light and shadow. This is the more primitive pathway providing the animal with quick and immediate reactions to food or danger—grab that banana or run—the ‘where and how’ pathway. The other pathway is for identification and future planning, simply called the ‘what’ pathway; it’s much slower because it can reach the thinking brain for deliberation—also the pathway where color is perceived. (The ‘where and how‘ pathway is known as the dorsal pathway; the ‘what’ pathway is the ventral pathway)

But let’s hear first from two early admirers of Cézanne: what exactly do they see in his art? What is this petite sensation?

The Beat poet Allen Ginsberg (US 1926-1997) was a big Cézanne fan and called this phenomenon the ‘eyeball kick’ in a 1956 interview in the Paris Review (scroll about one-third of the way down):

‘…there’s a sudden shift, a flashing that you see in Cézanne canvases. Partly it’s when the canvas opens up into three dimensions… like solid space objects… rather than flat… [The mysterious quality around his figures]…they look like great huge 3-d wooden dolls… Very uncanny…very mysterious… there’s a strange sensation that one gets… [Looking at his canvases], I began to associate with the extraordinary sensation—cosmic sensation…’

Alfred Barr (US 1902-1981), the art historian and founding director of MoMA (at age 27) included Cézanne in his first exhibition at MoMA in 1929 (see here my previous post). His observations of Cézanne would be more pragmatic—and understandable by us mere mortals. He says, in comparing Cézanne to Poussin (France 1594-1665) whose paintings inspired the artist (Exhibition catalogue p. 20-21) :

‘What did Cézanne really see in nature? Let him answer: “An optical sensation is produced in our eyes which makes us classify [grade] by light—half tones and quarter tones—each plane represented by a sensation of color.” He gives us here the key to the technical understanding of his later work… we find the paint broken up into a series of small planes, each one of which, especially in the landscapes, is made up of several subtly graded parallel strokes or hatchings. By this technique which Cézanne developed only after twenty years of painting he “realized” what he modestly called his “petite sensation”.’ [All italics mine]

So how was Cézanne a neuro-artist?

He found the ‘where and how’ neural pathway in our brain. He did so by holding the scene in his (and the viewer’s) peripheral vision —unconscious, mostly color-blind, and does not discern details in bright light—so as to see a holistic and broad structure of 3-dimensional forms: the rocks, trees, and leaves which he painted using different light and dark shadings. Thus his mountain appears to rise up towards the viewer. This is very important. It refutes the Renaissance gold standard of painting: the perspective in which the mountain would recede from the viewer—a logic of the ‘what’ pathway—the conscious.

His art is slow to paint and slower to appreciate because it’s hard for us to stay in the unconscious—it makes us defenseless—as if entering meditation.

Monet’s Impressionism had started this process by painting light and air, resulting in a shimmering vision of blurred and indefinite outlines: just impressions. According to Harvard neurobiologist Margaret Livingstone, Monet’s shimmering effects are the result of the uncertain division of labor between the two visual pathways in our brain, the struggle between form vs color perception:

‘Artists like Monet understood this dichotomy in our visual processes and used it empirically to give the illusion of color and space. The two parts are sometimes called the “where” and “what” system. The “where” system is the “colorblind” part that allows us to orient objects spatially, whereas the “what” system lets us recognize and evaluate them.’ *

Cézanne chose to stay with ‘form’, giving his painting real structure and ‘something solid and durable, like the art of the museums’, as he said.

So here comes the question: if our luminance perception for form is more primitive, more essential, why do we all see color first—and fuss so much over it?

More importantly, the deep unconscious understanding of structure and form could be the basis of physical and mathematical logic and reasoning. If so, our common thinking that the unconscious is neither structured nor rational may need a new examination. I will write next month about how the ‘where and how’ form pathway in our brain contains neurons that are activated during mathematical calculations.

* Color vs tone. See here photographer Mark Abeln’s Luminance is More Important than Color: A comparison of two versions of the same picture: one with luminance value (tone) removed; the other with color removed. You can see very clearly how much depth and structure is in the one without color. The color-only one looks like floating random blobs.