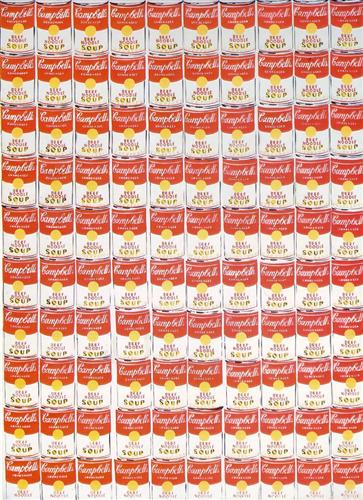

100 Cans (1962) Andy Warhol (US 1928 – 1987)

In my recent post here on Harvard University’s new admissions policy, I suggested the introduction of visual literacy education in primary schools in the US. But in fact, Arts Integration has been implemented in many schools around the US, and much written about, in the last decade.

One report from 2013, published in the Journal for Learning through the Arts, by Lisa LaJevic, Arts Integration: What is Really Happening in the Elementary Classroom? paints a bleak picture.

LaJevic found in her research a lack of teacher understanding of art—emphasizing visual pleasure: if it’s pretty, it’s good art: “Not only are the arts used for decorative purposes, but the arts component in Arts Integration is greatly diluted as well.”

On the other hand, there is mixed blessing in this success story from an Arts Magnet School, Bates Middle School in Annapolis, Maryland which began its arts integration program in 2007 with teacher education. After implementation in 2009, it has achieved notable outcomes:

“…English-language learners increased their achievement in math and reading by almost 30 percent. Special ed [sic] scores jumped higher than hoped.”

And the school is “developing a body of research data that shows that arts integration can help struggling students learn standard curricula”.

A look at its lesson plans (with plenty of open discussion online) indicates a creative and open culture of learning throughout. Some lessons use Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans painting to introduce the concept of fractions; or Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-strip-inspired paintings to talk about Pop art and looking. For some it may seem like art is being used as visual prop and memory aid though there’s nothing wrong with that—much of our learning is linear and conscious and requires efforts. But that cannot be the only way.

So for the art purists, the fact that art is being used as illustration or memory prop misses the point of art. And furthermore, the fact that the learning is goal and outcome-driven somewhat takes away the pleasure and the leisure of deep learning: the mind’s meandering and private scanning of a work of art. Hopefully that will come later—like in a museum.

My idea that schools could work more closely with museums, even conducting part of the curriculum there could make sense because more art resources could become available to facilitate learning. And it further ensures that arts integration does not take art into the utilitarian and singular realm of serving instant educational performance. As the French novelist Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) struggled in perfecting his art of expression, he felt that “Art is not in the service of man…it is man who is in the service of art.” Yes, the power to achieve a totality of the self within the world (beauty in Flaubert’s ideal) is art’s highest calling. And it should remain in the back of our minds whatever we do with it.